“We, Latin Americans, had a lot to do with the current wave of feminism.”

COHA (Council on Hemispheric Affairs), Washington D.C., March 7, 2018.

Interview with María José Lubertino

By Eugenia Rosales Matienzo

While feminism itself becomes increasingly mainstream, gender-based violence against women remains rampant throughout Latin America.[i]Femicide or feminicide are terms used to identify hate-crimes based on sex, broadly defined as “the intentional killing of women (or girls/children) solely because they are women.”[ii]

In the last decade in Argentina, 2,638 women were killed, or died for the sole reason of being women. 75 percent of the deaths were committed by men close to the victims, either family members, romantic partners or ex-partners. Nearly half of the victims lived with the assassin (65 percent of the femicides were committed in the house of the victim). Through legislation, the word Femicida (murderer of women) was incorporated in the Argentine Penal Code (Law 26.791) in 2012, typifying the homicide against women perpetrated by a man. Even though not all aggressions against women constitute this gruesome crime, it is a responsibility of the state to confront each and every sign of gender violence to protect potential victims and prevent femicide[iii].

Without a solution for this problem yet, many Argentinians actively demand that the government take specific measures to confront this social tragedy. An example is the emergence of the “Ni Una Menos” (Not One Less) movements, a mobilization that gave a name and voice to a feminist movement that protested violence against women, and its most extreme consequence, femicide. The Ni Una Menos march took place, for the first time, on June 3, 2015, throughout 80 Argentinian cities. Many countries have taken notice of the march and have organized their own manifestations, especially throughout Latin America.

COHA Research Associate Eugenia Rosales Matienzo interviewed María José Lubertino[iv], an Argentinian attorney and feminist leader. Lubertino was a former National Deputy, the former President of the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI), and a former Legislator for the City of Buenos Aires.

COHA: We have established that Argentina registered over 2,638 femicides between 2008 and 2017. Almost 300 women were killed in 2017 alone, meaning that the numbers of femicides have not been reduced in recent years. Is this a result of a lack of policies to eradicate gender violence has deepened with the change of government? What problematic open questions remain from the Kirchners’ administration?

Lubertino: Several policies were backed down which have a high incidence of materials of gender violence. For example, the dismantling of programs that have tackled sexual education and the inclusion of gender perspective from the Ministry of Education. Gender issues are entirely dependent on the minister of Social Development and continue to receive limited funding. The amount of femicides has increased and social mobilization has not received support from State policies nor a serious commitment from all the Ministries which are involved with women’s issues and with the Women Institute. There is no real political power, presence, or capacity of transversality with other departments.

I can see continuity in several of these issues because they have not been a priority during the previous administration. However, I believe that more social policies, from the previous government, was being addressed by the economic inclusion of women which facilitated their exit from their homes in a condition of autonomy. Policies such as those of inclusion for domestic workers, the possibility of retiring for housewives, the Universal Allocation per Child[v], and a series of other policies that provided autonomy for women to leave the house if there were victims of violence. What continues lacking is comprehensive and compulsory training on gender violence for state personnel, security forces, judicial workers, and professionals whose remit includes violence in any official dependencies of the state. This should not only be a national policy but, also implemented in all municipalities and provinces throughout Argentina. The best effort was made during Nilda Garre’s time as head of the Ministry of Security and Defense, but afterwards, it has not been seen in other areas of government.

Of course, many victims of femicidio lack effective judicial protections. Each prosecutor’s offices and every police station has lacked trained staff to properly process complaints. Also, guarantees are scarce regarding protection for the victims of violence, lack of implementation of electronic monitoring to ensure that the perpetrators do not violate the restriction orders implemented by the judicial system. There is a need for the establishment of full functioning offices to assist victims of domestic violence in all provinces (the National Supreme Court is the only department that currently has), and it is necessary for the objective of speeding up precautionary measures to protect the federalization of the telephone line 137. We need a better system of data complication and publication of official statistics regarding violence towards women, including an index for femicide.

The deepening and incorporation of sexual education with a gender perspective and gender violence and the arrangement of workshops to prevent violent relationships in all academic curriculums is required. This receded on the national level, and it was unevenly accomplished at the provincial level. There is a need for the construction of more homes and refuges for emergency, and housing subsidies with interdisciplinary assistance with a gender perspective. Also, there is a need for guarantees for the fulfillment of children’s rights with specialized legal sponsorship. Not all jurisdictions have ‘child advocates’. These would be some of the most important pending issues to be confronted.

COHA: Travesticidios (the murder of transvestites) have also increased in Argentina. Does it have to do with the hate towards the female gender?

Lubertino: I believe that it is here where we find accumulated all the irrational gender prejudices against “transphobia.” Meaning, it is here where we see a mixture of the hate towards gender with a specific hatred for those that do not cultivate hegemonic sexuality. Thus, I believe that this is what makes these travesticidios more violent. Obviously, they should be registered separately to see the incidence of transphobia, but, also, they should be included in the general statistics of feminicide. We are about to witness the first oral trial for the tranvesticide of Diana Sacayán. It would be the first time that a case of tranvesticides goes to court. Therefore, it is essential to follow what is said by the jurisprudence regarding the incident.

COHA: Are there any countries in Latin America that excel for their policies against gender violence or are their situations similar to Argentina?

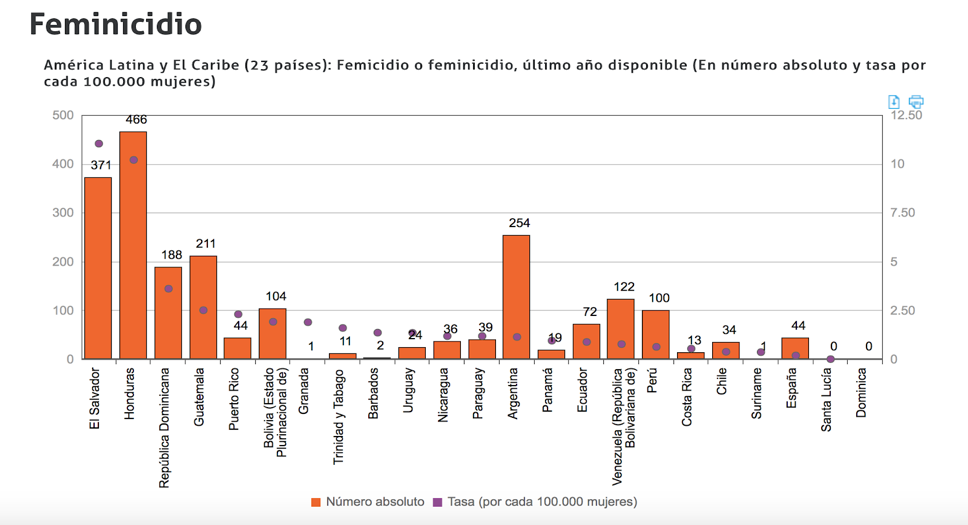

Lubertino: According to CEPAL’s graphs of gender observatory (see below), we can observe, from highest to lowest, both in absolute number as in rates of every 100 thousand women, what is the real situation. But Argentina is in the “platoon” of the intermediate countries. The only two countries that would be interesting and worth researching are Costa Rica and Chile because when you analyze the data, they are countries with fewer femicides. I don’t believe that machismo is any better in Chile than in other countries in Latin America, but, it is a fact that there are fewer femicides, or, at least, there is a possibility that there is a problem in the tabulation of these crimes. However, without a doubt, I could say, without looking at the statistics, that probably Costa Rica and Uruguay, because of the public policies they have sustained for a long time, they could have more favorable indicators. My hypothesis is confirmed in the case of Costa Rica, and not so much on the matter of Uruguay. I would emphasize the case of Uruguay for the legalization of abortion and for the public policies in the counseling pre and post-abortion, which I believe have helped demystify this topic and not incriminate women in all these cases.

COHA: A great debt from all governments is the access to legal, secure, and free abortions. What other policies should be urgently implemented regarding femicide and gender violence?

Lubertino: I believe that the most pressing issue is to establish an integral sexual education with gender perspective in the education system; more training for teachers, specifically for the early detection of gender violence; and, of course, we need municipal policies for citizens security and security of our cities for women with illumination and construction of safe cities for women. Similar proposals exist in cities like Buenos Aires, Rosario, and Córdoba, but the local governments do not always follow through with what the NGOs or citizens’ movements propose.

Another thing that I believe is fundamental is the image of women in the mass media. This requires consciousness from journalists and the mass media in their codes of ethics. Also, this is not a topic that can be imposed by law, but that could be incentivized through public policies. The observatory against discrimination against women that was created during my time in the INADI has gone through a scarce period with a limited role, only taking a more active part after a scandal erupts. Because of this, it is essential to integrate the women journalists in the organization of #NiUnaMenos and let them be the ones that lead this topic since they understand the language of the mass media and they belong to that “tribe.”

COHA: Concerning the prior mobilization of #NiUnaMenos, what was the effect of the Women International Strike which occurred on March 8?

Lubertino: From the feminist assembly we are planning the International Strike, and we are convinced that this is the year for legal, safe and free abortion.

The difference between the popular mobilization of #NiUnaMenos and previous movements is the massive involvement of many journalists and young people. This is a political construction from the women’s movements that go back to 1983. The movement began with a thousand members, and throughout its 31 years it has had of over 50 thousand women in attendance. This has strengthened many organization and has produced a strong movement with diverse political, economic, and ethnic belongings.

Therefore, more things unite us than divide us. These movements, #NiUnaMenos and the strike in Argentina are significant due to their massive size, political structure, organization, and their unity sustained on diversity. And, notably, I believe that the strength of the international strike is given through its international element, and how there is a collective construction of political processes throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America. But I believe, that from Latin America we had a lot to do with the resurgence of the current feminist wave.

COHA: Which slogans must be named this next March 8?

Lubertino: We most certainly will be addressing the same issues from last year’s strike, with several expansions in climate defense and several other problems that have taken precedence in the past year. They are slogans and demands, but also, they are policy proposals. It’s been 30 years with proposals not only of women rights, but also, of structural transformations in the current patriarchal economic system. These are transformations that are not seen as corporate demands, but as a benefit for society as a whole.

[i] MuMaLá Stats 2017.

[ii] Femicide or feminicide definition.

[iii] La Nación. 21 de noviembre, 2017.

[v] Universal Allocation Per Child (Asignación universal por hijo) is a social security program in Argentina.

Image: #NI UNA MENOS on Argentina’s Flag Taken from: Pxhere.com